The Value of Expertise

I might get myself in trouble with this one.

As a teacher (and especially when I worked in “regular” ed), I’ve heard the following line more than once from parents: “I know what’s best for my child.”

Really? If so, why do we have pediatricians? Dentists? Why send children to school at all, where they’ll be taught by someone who is not the parent of said-child?

We trust that doctors know more than we do about physical health. Most of us take our cars to mechanics because they know more about engines and carburetors and serpentine belts than we do. They have something we don’t—EXPERTISE on the subject.

Same goes for teaching. I studied enough about mathematics and the teaching thereof to earn two degrees. I’ve taught just about every level of math that exists in secondary education. Perhaps I know a thing or two.

That’s not to say parents (or anyone) should blindly trust the experts. But to make an informed argument, they need to gain some expertise of their own.

Ask questions. Do some research. Try a few different things—that would definitely make you an expert on what has and hasn’t worked in the past. Make sure you understand the reasoning behind the advice being given to you before you dismiss it.

Wait a minute. This sounds familiar.

It applies to writing, too.

Writers often say we know what’s best for our stories. In some ways, yes … but in some, maybe not. Does the writer have the expertise to make that judgment?

An editor or agent generally does have that expertise. They’ve studied, trained, and had experience in the world of writing. They might just know more than we do about what does or doesn’t work. (Yes, it’s a very subjective industry, but some things are clear-cut enough.)

Agents are too overwhelmed to give much feedback, and most of us don’t have access to an editor, nor the means to pay a freelancer. So we’re left to gain at least some expertise ourselves.

How can we do that? I have friends who’ve been through MFA programs, and it shows in both the polish and cohesive structure of their work. But that may not be the route for all of us. There are How-To books of various types. Expertise galore, ready for us to access it.

Reading can be a great way, too, but we can’t just read. We have to read on a “meta” level. When we enjoy something, we need to think about why—what did the author do right, and how? If something annoys or bores us, we need to figure out what’s behind that, too.

Will all of that ever equal the knowledge and experience an industry pro can bring to the table? Probably not. But that’s where strength in numbers comes in. Solid critique partners who’ve also done their part to gain expertise can have a huge effect on our outcome. (More on that coming on a special post August 15th.)

The bottom line is that we shouldn’t plug our ears and chant that we know what’s best for the story simply because we wrote it.

Well, really, we can do anything we want in our novels … if we don’t care about getting published.

Math Geek Meets Novelist

No one’s shocked by the declaration that I’m a math geek who happens to write, right? Sometimes the math-geekiness informs my writing with character quirks or the way I apply logic. These are relatively small ways, where creativity and command of the language still play a larger role.

Once in a while, though, the geek takes over, and graphs ensue.

Really, this makes sense. The main reason graphs exist is to give us an instant visual of the big picture. Since a novel is hundreds of manuscript pages, it’s pretty difficult to look at it all at once as a whole.

What kinds of graphs? I’ll share a couple. (You can click them and get a better look.)

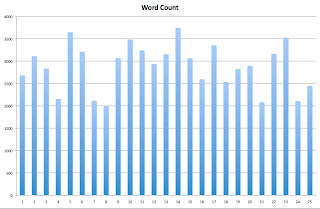

The first is a bar graph I made early on in my writing life to see how much my chapter lengths were varying. (Yes, this was also a case of my number-OCD coming out to play.) Nothing too fancy, just a simple graph in Excel.

I haven’t done one of these for my more recent manuscripts, but it gave me some thoughts about overall structure when I was first starting. Interesting note: the manuscript graphed here had twenty-five chapters at the time, but I eventually realized breaking some of them up worked better.

The second is one I just did for the first time this week as an experiment. I was curious how different plot “threads” or themes were distributed throughout the novel. Had I dropped a thread in and then neglected it for too long before it came up again? Were the key themes getting the amount of attention I feel they deserve?

So I listed three key threads, two secondary (sort of) ones, and a trait of the MC I wanted to make sure had been sprinkled consistently through the story. Then I started reading and noting the location where each item pops up or is addressed (shown as a percentage, i.e., 25% of the way through the novel). I made the graph using a middle school statistics program called Tinkerplots (yay for being a math teacher!), though something similar could be made using Excel … I think it’d just be a little more complicated.

I’m pretty pleased with the results. The three main threads obviously have sections where they each take precedence, and the “sprinkling in” looks pretty much how I want it.

Yes, I’m a geek.

Have you ever analyzed your writing in a “non-writing” way? Have you applied your day-job skills to something unexpected?

If You Think It’s Easy, You’re Probably Doing It Wrong

DISCLAIMER: I have not self-published (yet … I know, I keep saying that). That said, I’ve gone through a lot of the necessary processes—practicing, if you will. I’ve played with designing covers, some of which you can also see by clicking the title tabs at the top of the page. I’ve done interior formatting and had proof copies made. I’ve made eBooks in both EPUB and MOBI formats (not just preparing my Word doc for some company’s automated conversion process—I figured out how to do it myself).

So that’s the headspace the following chunk of opinion comes from.

There’s a lot of buzz lately about literary agents forming e-publishing wings. Some are set up more to facilitate their existing clients’ self-publishing efforts, while others seek to be full-fledged publishers. The latest is over at Bookends, with lots of very passionate responses on both sides of the is-it-ethical and is-it-smart debates.

I’m not going to weigh in on those aspects. People far more intelligent and experienced than I are already doing that. But there’s a particular idea in the responses that I’ve seen many times. Not just there—I’ve seen it in various writing forums whenever self/e-publishing comes up:

“Do it yourself. It’s easy.”

Okay, the physical act of uploading your manuscript to Amazon, B&N, or Smashwords is easy. But I’ve been scoping out the results, and it’s clear many writers are missing the truth:

Doing it is easy. Doing it well is hard.

Forget the trials of marketing, getting anyone to even find your book among the many on Kindle. I’m just talking about the front-end job of getting it prepped for daylight. Let’s look at the aspects that as a reader make me tear my hair out.

* * * * *

COVERS

Oh, my … covers. My brother is a graphic designer. I don’t know nearly as much as he does, but I’ve absorbed a few things through conversations with him. And I’m not saying my covers are super-fabulous—remember, I’m just playing and experimenting so far. (But an editor at HarperCollins did compliment my Fingerprints cover. *blush*)

Do you honestly have a good eye for design? Or do you think most things look “good enough”? Scanning the Kindle listings, it’s not hard to spot a “homemade” cover. (And I will say, certain smaller publishers aren’t much better with their cover designs.) If you’ve cut elements from different images and stuck them together, have you really made it look like one seamless whole that was meant to be that way?

In most cases, no.

So, what to do? Pay for a graphic designer? Maybe. But if so, beware. I’ve seen freelance graphic designers with credentials and everything who create crap cover designs. If you’re paying far less than $100, you might get a very nice (but basic) cover, or you might get something my high school students could out-do during their lunch break.

If you want something really high-quality, that doesn’t scream DIY from a mile away, you have some options. Invest some real money in it. Have/develop the skills and tools yourself. Or be lucky enough to know someone with the talent who’s willing to do you a favor.

And for goodness sake, make sure you have the proper rights to use any stock images you need. Just because you found it on the internet and did a right-click/save doesn’t mean it’s fair game. Same goes for fonts. (You didn’t know you can’t just use whatever fonts you have installed on your computer? Go do some homework.)

* * * * *

E-FORMATTING

I’ve already done a full rant on this subject before, so I’ll just reiterate a few things.

If you use a meat-grinder, you get hamburger … not steak.

Maybe you like hamburger. If you do it very carefully and make sure the “meat” going in has everything just right, you might be able to get a five-star, gourmet burger out of it.

Personally, I have a hard time trusting automated conversions, even specialized ones like Kindle uses. I really don’t trust an automated process that takes one file and spits out five or six different formats. You don’t have to be a control freak like me, but triple-check your results in ALL formats to make sure the result is pristine.

* * * * *

EDITING

Oh, yeah, this is about a story people will (hopefully) read.

This is the biggest roadblock for many. To get the kind of intense, whip-it-into-shape editing my friends with Big-6 publishing deals have gone through, you would have to spend more than $1000. It’s not just proofreading, though some of the errors and typos I’ve seen in self-pub’d works still make me shudder. Here’s a little story to illustrate:

Once upon a time, there was a novel posted at an online writers’ community. I read the first few chapters and thought it was marvelous. Surely this would be picked up by an agent. Surely it had a better shot than most at being published.

Alas, it did not happen. Eventually, the author decided to self-publish. I remembered loving what I read, so I gladly made the purchase.

As I read the whole thing, I was heartbroken. It quickly became obvious why it didn’t make it on the traditional route. Nothing to do with the mechanics of the writing; everything to do with the craft of the story. Repetitive recaps every time a new character entered the picture. Disbelief that could no longer be suspended even by a reader eager to love the story (such as myself).

There are those who say you can edit well enough if you have a good critique group. I believe that can be true. But is your critique group tough enough on you? Do they know enough to spot overarching problems, or are they just good for helping you polish and tighten sentences?

If you can’t afford a 4-digit editing bill (and really, how many of us can?) there are other options. Read with a critical eye, not just for the words on the page, but how the story is shaped and woven together. Look at some books on craft until you find some that work for your style, genre, etc. Maybe take a class or two.

And if you’re lucky enough to find critique partners who really know what they’re talking about and can tear your work apart in a way that makes you thank them for the torture … dig your claws in and never let them go.

* * * * *

I’m sure I’ve only scratched the surface of what goes into making a self-published book top-notch. It’s NOT easy. (Neither is going the traditional route.) It doesn’t mean you necessarily have to spend your life savings. It does mean you should work your tail off … and put in some major time between finishing the “writing” part and putting the product on the market.

Is it worth it? After all, you’re probably only charging around $1-5 for your eBook, right? Maybe you’re embracing the concept of a pulp fiction revival and are glad to be a part of it.

That’s great. But I say you should still respect your readers enough to make sure anything you put in front of them is nothing less than awesome.

Did I miss anything? Other pet-peeves in self-published work? Or am I just way too picky? 😉

Why Everyone Should Learn Sign Language

Seriously.

I’ve thought this before, but it hit me again this morning. Every Tuesday this summer, I’ve been helping my dad work on their backyard. Today, we cut big landscape blocks in half. (BTW, 12-inch concrete saw with diamond blade? Awesome.) Being good little workers, we wore safety glasses and earplugs.

Have you ever tried to talk to someone while you’re both wearing earplugs? Better yet, while a power saw is running? How much easier would it be if my dad knew sign language?

And that’s not the only situation where it would be handy. Other times, my dad’s been down in the walkout from the basement while I’m above in the backyard, and the A/C is running nearby. Very hard to hear what he’s saying.

Then there’s my favorite: restaurants. I love going out with deaf friends and colleagues. Doesn’t matter how noisy it gets, conversation is still just as easy to follow. One time, there was a full mariachi band in the room, but we kept chatting away. No problem.

When I’m out with non-signers and the restaurant’s noisy/the acoustics are lousy? All I can think is, “If only!”

Oh, and if you make the acquaintance of a deaf person (who signs)? Bonus! Easy communication.

To my international friends, though, sorry. Your sign language isn’t my sign language, unless you’re in Canada (but not Quebec). Yes, different countries have different sign languages. (I know this is a shocker to some.)

Can you guys think of any situations where it’d be nice if everyone involved knew sign language?

Blog Contests: Getting Back on the Horse

There’s a pitch contest over at Chanelle Gray’s blog starting today and going until July 25th (or until they hit 150 entries, whichever comes first). First line, two-sentence pitch, and literary agent Victoria Marini.

I got a little shaken up the last time I entered a blog contest (different from this one, and it was ages ago), but it’s about time I shake it off and try again. After all, what have I got to lose?

What experiences have you guys had—good, bad, or ugly—with blog contests?

Imperfection vs. Idiocy

Here’s another case where something I noticed as a reader has carried over to my writing. Flawed characters are a good thing. Perfect characters are boring, not to mention severely unrealistic. If characters are perfect and always do the right thing, there’s no interest and frequently no story.

Like everything else, though, flawed characters can go to an extreme that doesn’t work any better. A student of mine (now graduated) probably shouldn’t ever get an e-reader, because judging by our conversations, I think she may tend toward throwing books across the room. Or at least slamming them down on a desk.

The reason? Idiotic protagonists.

This is particularly prevalent in certain YA novels (or at least, that’s where I notice it, since it’s the world I know). Teenagers are in a stage of life that’s naturally more self-centered, and maybe that leads to the idea of making dumb decisions.

Okay, we all make bad decisions. That’s normal. But a character’s bad decision should be something that a real person would really do under those circumstances. More particularly, the bad decision should be consistent with what’s known about the character … not just something that’s convenient for the plot. (Hmm, I think that goes back to my post on front-end/back-end motivation, too.)

Here’s the thing. I’ve only known one teen in my whole life (including when I was a teen) who seemed to be 100% self-interested in their actions. And in that case, a personality disorder was likely. I also have a hard time thinking of any teens who act outright stupid in the way some novel characters do.

A cohort of the super-self-interested character is the one with false selflessness. The one who supposedly does what she does because she loves the boy, or wants to keep her friends safe. But when you look at it, the actions don’t match the supposed motivation. The character is just being stupid … because it’s convenient.

So where’s the line and the balance? How do we instill our characters with realistic, interesting flaws (and appropriately get them in trouble) without our teen readers thinking we’re insulting the intelligence of their species?